Using CTEs and Query Rewriting for Versioning

Joist is an ORM primarily developed for Homebound’s GraphQL majestic monolith, and we recently shipped a long-awaited Joist feature, SQL query rewriting via an ORM plugin API, to deliver a key component of our domain model: aggregate level versioning.

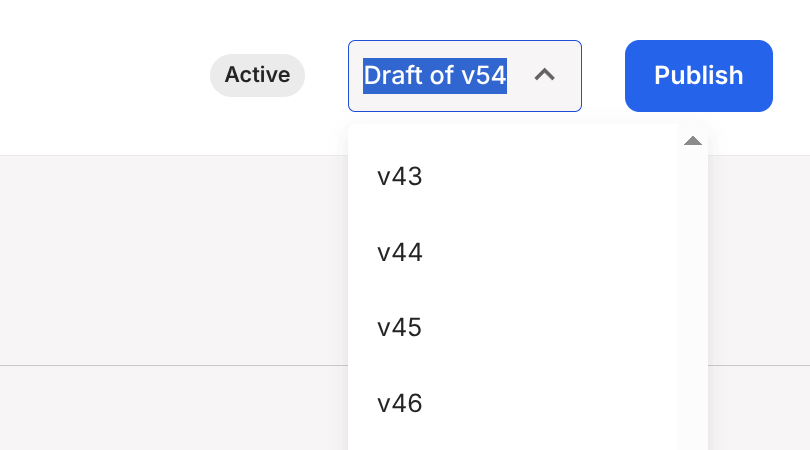

We’ll get into the nuanced details below, but “aggregate level versioning” is a fancy name for providing this minor “it’s just a dropdown, right? 😰” feature of a version selector across several major subcomponents of our application:

Where the user can:

- “Time travel” back to a previous version of what they’re working on ⌛,

- Draft new changes (collaboratively with other users) that are not seen until they click “Publish” to make those changes active ✅

And have the whole UI “just work” while they flip between the two.

As a teaser, after some fits & painful spurts, we achieved having our entire UI (and background processes) load historical “as of” values with just a few lines of setup/config per endpoint—and literally no other code changes. 🎉

Read on to learn about our approach!

Aggregate What Now?

Section titled “Aggregate What Now?”Besides just “versioning”, I called this “aggregate versioning”—what is that?

It’s different from traditional database-wide, system time-based versioning, that auditing solutions like cyanaudit or temporal FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF queries provide (although we do use cyanaudit for our audit trail & really like it!).

Let’s back up and start with the term “aggregate”. An aggregate is a cluster of ~2-10+ “related entities” in your domain model (or “related tables” in your database schema). The cluster of course depends on your specific domain—examples might be “an author & their books”, or “a customer & their bank accounts & profile information”.

Typically there is “an aggregate parent” (called the “aggregate root”, since it sits at the root of the aggregate’s subgraph) that naturally “owns” the related children within the aggregate; i.e. the Author aggregate root owns the Book and BookReview children; the Customer aggregate root owns the CustomerBankAccount and CustomerProfile entities.

Historically, Aggregate Roots are a pattern from Domain Driven Design, and mostly theoretically useful—they serve as a logical grouping, which is nice, but don’t always manifest as specific outcomes/details in the implementation (at least from what I’ve seen).

Why Version An Aggregate?

Section titled “Why Version An Aggregate?”Normally Joist blog posts don’t focus on specific domains or verticals, but for the purposes of this post, it helps to know the problem we are solving.

At Homebound, we’re a construction company that builds residential homes; our primary domain model supports the planning and execution of our procurement & construction ops field teams.

The domain model is large (currently 500+ tables), but two key components are:

- The architectural plans for a specific model of home (called a

PlanPackage), and - The design scheme for products that go into a group of similar plans (called a

DesignPackage)—i.e. a “Modern Farmhouse” design package might be shared across ~4-5 separate, but similarly-sized/laid out, architectural plans

Both of these PlanPackages and DesignPackages are aggregate roots that encompass many child PlanPackage... or DesignPackage... entities within them:

- What rooms are in the plan?

PlanPackageRooms - What materials & labor are required (bricks, lumber, quantities)?

PlanPackageScopeLines - What structural/floor plan options do we offer to customers?

PlanPackageOptions- How do these options change the plan’s materials & labor? A m2m between

PlanPackageScopeLines andPlanPackageOptions

- How do these options change the plan’s materials & labor? A m2m between

- What are the appliances in the kitchen?

DesignPackageProducts - What spec levels, of Essential/Premium/etc, do we offer?

DesignPackageOptions- How do these spec levels change the home’s products? A m2m between

DesignPackageProducts andDesignPackageOptions

- How do these spec levels change the home’s products? A m2m between

This web of interconnected data can all be modeled successfully (albeit somewhat tediously)—but we also want it versioned! 😬

Change management is extremely important in construction—what was v10 of the PlanPackage last week? What is v15 of the PlanPackage this week? What changed in each version between v10 and v15? Are there new options available to homebuyers? What scope changed? Do we need new bids? Etc.

And, pertintent to this blog post, we want each of the PlanPackages and DesignPackages respective “web of interconnected data” (the aggregate root & its children) versioned together as a group with application-level versioning: multiple users collaborate on the data (making simultaneous edits across the PlanPackage or DesignPackage), co-creating the next draft, and then we “Publish” the next active version with a changelog of changes.

After users draft & publish the plans, and potentially start working on the next draft, our application needs to be able to load a complete “aggregate-wide snapshot” for “The Cabin Plan” PlanPackage v10 (that was maybe published yesterday) and a complete “aggregate-wide snapshot” of “Modern Design Scheme” DesignPackage v8 (that was maybe published a few days earlier), and glue them together in a complete home.

Hopefully this gives you an idea of the problem—it’s basically like users are all collaborating on “the next version of the plan document”, but instead of it being a single Google Doc-type artifact that gets copy/pasted to create “v1” then “v2” then “v3”, the collaborative/versioned artifact is our deep, rich domain model (relational database tables) of construction data.

Schema Approach

Section titled “Schema Approach”After a few cough “prototypes” cough of database schemas for versioning in the earlier days of our app, we settled on a database schema we like: two tables per entity, a main “identity” table, and a “versions” table to store snapshots, i.e. something like:

authorstable: stores the “current” author data (first_name,last_name, etc), with 1 row per author (we call this the “identity” table)author_versionstable: stores snapshots of the author over time (author_id,version_id,first_name,last_name), with 1 row per version of each author (we call this the “version” table)

This is an extremely common approach for versioning schemas, i.e. it’s effectively the same schema suggested by PostgreQL’s SQL2011Temporal docs, albeit technically they’re tracking system time, like an audit trail, and not our user-driven versioning.

This leads to a few differences: the SQL2011Temporal history tables use a _system_time daterange column to present “when each row was applicable in time” (tracking system time), while we use two FKs that also form “an effective range”, but the range is not time-based, it’s version-based: “this row was applicable starting at first=v5 until final=v10”.

So if we had three versions of an Author in our author_versions table, it would look like:

id=10 author_id=1 first_id=v10 final_id=v15 first_name=bob last_name=smith- From versions

v10tov15, theauthor:1had afirstName=bob

- From versions

id=11 author_id=1 first_id=v15 final_id=v20 first_name=fred last_name=smith- From versions

v15tov20, theauthor:1had afirstName=fred

- From versions

id=11 author_id=1 first_id=v20 final_id=null first_name=fred last_name=brown- From versions

v20to now, theauthor:1had alastName=brown

- From versions

We found this _versions table strikes a good balance of tradeoffs:

- It only stores changed rows—if

v20of the aggregate root (i.e. ourPlanPackage) only changed theAuthors and two of itsBooks, there will only be 1author_versionsand twobook_versions, even if the Author has 100s of books (i.e. we avoid making full copies of the aggregate root on every version) - When a row does change, we snapshot the entire row, instead of tracking only specific columns changes (storing the whole row takes more space, but makes historical/versioned queries much easier)

- Technically we only include mutable columns in the

_versionstable, i.e. our entities often have immutable columns (liketypeflags orparentreferences) and we don’t bother copying these into the_versionstables.

- Technically we only include mutable columns in the

- We only store 1 version row “per version”—i.e. if, while making

PlanPackagev20, anAuthors first name changes multiple times, we only keep the latest value in the draftauthor_versionss row.- This is different from auditing systems like SQL2011Temporal, where

_historyrows are immutable, and every change must create a new row—we did not need/want this level of granularity for our application-level versioning.

- This is different from auditing systems like SQL2011Temporal, where

With this approach, we can reconstruct historical versions by finding the singular “effective version” for each entity, with queries like:

select * from author_versions avjoin authors a on av.author_id = a.idwhere a.id in ($1) and av.first_id <= $2 and (av.final_id is null or av.final_id < $3)Where:

$1is whatever authors we’re looking for (here a simple “id matches”, but it could be an arbitrarily complexWHEREcondition)$2is the version of the aggregate root we’re “as of”, i.e. v10$3is also the same version “as of”, i.e. v10

The condition of first_id <= v10 < final_id finds the singular author_versions row that is “effective” or “active” in v10, even if the version itself was created in v5 (and either never replaced, or not replaced until “some version after v10” like v15).

…but what is “Current”?

Section titled “…but what is “Current”?”The authors and author_versions schema is hopefully fairly obvious/intuitive, but I left out a wrinkle: what data is stored in the authors table itself?

Obviously it should be “the data for the author”…but which version of the author? The latest published data? Or latest/WIP draft data?

Auditing solutions always put “latest draft” in authors, but that’s because the application itself is always reading/writing data from authors, and often doesn’t even know that the auditing author_versions tables exist—but in our app, we need workflows & UIs to regularly read “the published data” & ignore the WIP draft changes.

So we considered the two options:

- The

authorstable stores the latest draft version (as in SQL2011Temporal), or - The

authorstable stores the latest published version,

We sussed out pros/cons in a design doc:

- Option 1. Store “latest draft” data in

authors- Pro: Writes with business logic “just read the Author and other entities” for validation

- Con: All readers, even those that just want the published data, must use the

_versionstable to “reconstruct the published/active author”

- Option 2. Store the “latest published” data in

authors- Pro: The safest b/c readers that “just read from

authors” will not accidentally read draft/unpublished data (a big concern for us) - Pro: Any reader that wants to “read latest” doesn’t have to know about versioning at all, and can just read the

authorstable as-is (also a big win) - Con: Writes that have business logic must first “reconstruct the draft author” (and its draft books and its draft book reviews if apply cross-entity business rules/invariants) from the

_versionstables

- Pro: The safest b/c readers that “just read from

This “reconstruction” problem seemed very intricate/complicated, and we did not want to update our legacy callers (which were mostly reads) to “do all this crazy version resolution”, so after the usual design doc review, group comments, etc., we decide to store latest published in authors.

The key rationale being:

- We really did not want to instrument our legacy readers to know about

_versionstables to avoid seeing draft data (we were worried about draft data leaking into existing UIs/reporting) - We thought “teaching the writes to ‘reconstruct’ the draft subgraph” when applying validation rules would be the lesser evil.

(You can tell I’m foreshadowing this was maybe not the best choice.)

Initial Approach: Not so great

Section titled “Initial Approach: Not so great”With our versioning scheme in place, we started a large project for our first versioning-based feature: allowing home buyers to deeply personalize the products (sinks, cabinet hardware, wall paint colors, etc) in the home their buying (i.e. in v10 of Plan 1, we offered sinks 1/2/3, but in v11 of Plan 1, we now offer sinks 3/4/5).

And it was a disaster.

This new feature set was legitimately complicated, but “modeling complicated domain models” is supposed to be Joist’s sweet spot—what was happening?

We kept having bugs, regressions, and accidental complexity—that all boiled down to the write path (mutations) having to constantly “reconstruct the drafts” that it was reading & writing.

Normally in Joist, a saveAuthor mutation just “loads the author, sets some fields, and saves”. Easy!

But with this versioning scheme:

- the

saveAuthormutation has to first “reconstruct the latest-draftAuthorfrom theauthor_versions(if it exists) - any writes cannot be “just update the

Authorrow” (that would immediately publish the change), they need to be staged into the draftAuthorVersion - any Joist hooks or validation rules also need to do the same thing:

- validation rules have to “reconstruct the draft” view of the author + books + book reviews subgraph of data they’re validating,

- hooks that want to make reactive changes must also “stage the change” into a draft

BookVersionorBookReviewVersioninstead of “just setting someBookfields”.

We had helper methods for most of these incantations—but it was still terrible.

After a few months of this, we were commiserating about “why does this suck so much?” and finally realized—well, duh, we were wrong:

We had chosen to “optimize reads” (they could “just read from authors” table).

But, in doing so, we threw writes under the bus—they needed to “read & write from drafts”—and it was actually our write paths that are the most complicated part of our application—validation rules, side effects, business process, all happen on the write path.

We needed the write path to be easy.

New Approach: Write to Identities

Section titled “New Approach: Write to Identities”We were fairly ecstatic about reversing direction, and storing drafts/writes directly in authors, books, etc.

This would drastically simplify all of our write paths (GraphQL mutations) back to “boring CRUD” code:

// Look, no versioning code!const author = await em.load(Author, "a:1");if (author.shouldBeAllowedToUpdateFoo) { author.foo = 1;}await em.flush();…but what about those reads? Wouldn’t moving the super-complicated “reconstruct the draft” code out of the writes (yay!), over into “reconstruct the published” reads (oh wait), be just as bad, or worse (which was the rationale for our original decision)?

We wanted to avoid making the same mistake twice, and just “hot potato-ing” the write path disaster over to the read path.

Making Reads not Suck

Section titled “Making Reads not Suck”We spent awhile brainstorming “how to make our reads not suck”, specifically avoiding manually updating all our endpoints’ SQL queries/business logic to do tedious/error-prone “remember to (maybe) do version-aware reads”.

If you remember back to that screenshot from the beginning, we need our whole app/UI, at the flip of a dropdown, to automatically change every SELECT query from:

-- simple CRUD querySELECT * FROM authors WHERE id IN (?) -- or whatever WHERE clauseTo a “version-aware replacement”:

-- find the right versions rowSELECT * FROM author_versions avWHERE av.author_id in (?) -- same WHERE clause AND av.first <= v10 -- and versioning AND (av.final IS NULL or av.final > v10)And not only for top-level SELECTs but anytime authors is used in a query, i.e. in JOINs:

-- simple CRUD query that joins into `authors`SELECT b.* FROM books JOIN authors a on b.author_id = a.id WHERE a.first_name = 'bob';

-- version-aware replacement, uses books_versions *and* author_versions-- for the join & where clauseSELECT bv.* FROM book_versions bv -- get the right author version JOIN author_versions av ON bv.author_id = av.author_id AND (av.first <= v10 AND (av.final IS NULL or a.final > v10)) -- get the right book version WHERE bv.first <= v10 AND (bv.final IS NULL or bv.final > v10) -- predicate should use the version table AND av.first_name = 'bob';1. Initial Idea: Using CTEs

Section titled “1. Initial Idea: Using CTEs”When it’s articulated like “we want every table access to routed to the versions table”, a potential solution starts to emerge…

Ideally we want to magically “swap out” authors with “a virtual authors table” that automatically has the right version-aware values. How could we do this, as easily as possible?

It turns out a CTE is a great way of structuring this:

-- create the fake/version-aware authors tableWITH _authors ( SELECT -- make the columns look exactly like the regular table av.author_id as id, av.first_name as first_name -- but read the data from author_versions behind the scenes FROM author_versions WHERE (...version matches...))-- now the rest of the application's SQL query as normal, but we swap out-- the `authors` table with our `_authors` CTESELECT * FROM _authors aWHERE a.first_name = 'bob'And that’s (almost) it!

If anytime our app wants to “read authors”, regardless of the SQL query it’s making, we swapped authors-the-table to _authors-the-CTE, the SQL query would “for free” be using/returning the right version-aware values.

So far this is just a prototype; we have three things left to do:

- Add the request-specific versioning config to the query

- Inject this rewriting as seamlessly as possible

- Evaluate the performance impact

2. Adding Request Config via CTEs

Section titled “2. Adding Request Config via CTEs”We have a good start, in terms of a hard-coded prototype SQL query, but now we need to get the first <= v10 AND ... pseudo code in the previous SQL snippets actually working.

Instead of a hard-coded v10, we need queries to use:

- Dynamic request-specific versioning (i.e. the user is currently looking at, or “pinning to”,

PlanPackagev10), and - Support pinning multiple different aggregate roots in the same request (i.e. the user is looking at

PlanPackagev10 butDesignPackagev15)

CTEs are our new hammer 🔨—let’s add another for this, calling it _versions and using the VALUES syntax to synthesize a table:

WITH _versions ( SELECT plan_id, version_id FROM -- parameters added to the query, one "row" per pinned aggregate -- i.e. `[1, 10, 2, 15]` means this request wants `plan1=v10,plan2=v15` VALUES (?, ?), (?, ?)), _authors ( -- the CTE from before but joins into _versions for versioning config SELECT av.author_id as id, av.first_name as first_name FROM authors a JOIN _versions v ON a.plan_id = v.plan_id -- now we know: -- a) what plan the author belongs to (a.plan_id, i.e. its aggregate root) -- b) what version of the plan we're pinned to (v.version_id) -- so we can use them in our JOIN clause JOIN author_versions av ON ( av.author_id = a.id AND av.first_id >= v.version_id AND ( av.final_id IS NULL OR av.final_id < v.version_id ) ))SELECT * FROM _authors a WHERE a.first_name = 'bob'Now our application can “pass in the config” (i.e. for this request, plan:1 uses v10, plan:2 uses v15) as extra query parameters into the query, they’ll be added as rows to the _versions CTE table, and then the rest of the query will resolve versions using that data.

Getting closer!

One issue with the query so far is that we must ahead-of-time “pin” every plan we want to read (by adding it to our _versions config table), b/c if a plan doesn’t have a row in the _versions CTE, then the INNER JOINs will not find any p.version_id available, and none of its data will match.

Ideally, any plan that is not explicitly pinned should have all its child entities read their active/published data (which will actually be in their author_versions tables, and not the primary authors tables); which we can do with (…wait for it…) another CTE:

WITH _versions ( -- the injected config _versions stays the same as before SELECT plan_id, version_id FROM VALUES (?, ?), (?, ?)), _plan_versions ( -- we add an additional CTE that defaults all plans to active unless pinned in _versions SELECT plans.id as plan_id, -- prefer `v.version_id` but fallback on `active_version_id` COALESCE(v.version_id, plans.active_version_id) as version_id, FROM plans LEFT OUTER JOIN _versions v ON v.plan_id = plans.id)_authors ( -- this now joins on _plan_versions instead _versions directly SELECT av.author_id as id, av.first_name as first_name FROM authors a JOIN _plan_versions pv ON a.plan_id = pv.id JOIN author_versions av ON ( av.author_id = a.id AND av.first_id >= pv.version_id AND ( av.final_id IS NULL OR av.final_id < pv.version_id ) ))-- automatically returns & filters against the versioned dataSELECT * FROM _authors a WHERE a.first_name = 'bob'We’ve basically got it, in terms of a working prototype—now we just need to drop it into our application code, ideally as easily as possible.

3. Injecting the Rewrite Automatically

Section titled “3. Injecting the Rewrite Automatically”We’ve discovered a scheme to make reads automatically version-aware—now we want our application to use it, basically all the time, without us messing up or forgetting the rewrite incantation.

Given that a) we completely messed this up the 1st time around 😕, and b) this seems like a very mechanical translation 🤖, what if we could automate it? For every read?

Our application already does all reads through Joist (of course 😅), as EntityManager calls:

// Becomes SELECT * FROM authors WHERE id = 1const a = em.load(Author, "a:1");// Becomes SELECT * FROM authors WHERE first_name = ?const as = em.find(Author, { firstName: "bob" });// Also becomes SELECT * FROM authors WHERE id = ?const a = await book.author.load();It would be really great if these em.load and em.find SQL queries were all magically rewritten—so that’s what we did. 🪄

We built a Joist plugin that intercepts all em.load or em.find queries (in a new plugin hook called beforeFind), and rewrites the query’s ASTs to be version-aware, before they are turned into SQL and sent to the database.

So now what our endpoint/GraphQL query code does is:

function planPackageScopeLinesQuery(args) { // At the start of any version-aware endpoint, setup our VersioningPlugin... const plugin = new VersioningPlugin(); // Read the REST/GQL params to know which versions to pin const { packageId, versionId } = args; plugin.pin(packageId, versionId); // Install the plugin into the EM, for all future em.load/find calls em.addPlugin(plugin);

// Now just use the em as normal and all operations will automatically // be tranlated into the `...from _versions...` SQL const { filter } = args; return em.find(PlanPackageScopeLine, { // apply filter logic as normal, pseudo-code... quantity: filter.quantity, });}How does this work?

Internally, Joist parses the arguments of em.find into an AST, ParsedFindQuery, that is a very simplified AST/ADT version of a SQL query, i.e. the shape looks like:

// An AST/ADT for an `em.find` call that will become a SQL `SELECT`type ParsedFindQuery = { // I.e. arrays of `a.*` or `a.first_name` selects: ParsedSelect[]; // I.e. the `authors` table, with its alias, & any inner/outer joins tables: ParsedTable[]; // I.e. `WHERE` clauses condition?: ParsedExpressionFilter; groupBys?: ParsedGroupBy[]; orderBys: ParsedOrderBy[]; ctes?: ParsedCteClause[];};After Joist takes the user’s “fluent DSL” input to em.find and parses it into this ParsedFindQuery AST, plugins can now inspect & modify the query:

class VersioningPlugin { // List of pinned plan=version tuples, populated per request #versions = []

// Called for any em.load or em.find call beforeFind(meta: EntityMetadata, query: ParsedFindQuery): void { let didRewrite = false; for (const table of [...query.tables]) { // Only rewrite tables that are versioned if (hasVersionsTable(table)) { this.#rewriteTable(query, table); didRewrite = true; } } // Only need to add these once/query if (didRewrite) { this.#addCTEs(query); } }

#rewriteTable(query, table) { // this `table` will initially be the `FROM authors AS a` from a query; // leave the alias as-is, but swap the table from "just `authors`" to // the `_authors` CTE we'll add later table.table = `_${table.table}`;

// If `table.table=author`, get the AuthorMetadata that knows the columns const meta = getMetadatFromTableName(table.table);

// Now inject the `_authors` CTE that to be our virtual table query.ctes.push({ alias: `_${table.table}`, columns: [...], query: { kind: "raw", // put our "read the right author_versions row" query here; in this blog // post it is hard-coded to `authors` but in the real code would get // dynamically created based on the `meta` metadta sql: ` SELECT av.author_id as id, av.first_name as first_name, -- all other author columns... FROM authors a JOIN _plan_versions pv ON a.plan_id = pv.id JOIN author_versions av ON ( av.author_id = a.id AND av.first_id >= pv.version_id AND ( av.final_id IS NULL OR av.final_id < pv.version_id ) ) ` } }) }

// Inject the _versions and _plan_versions CTEs #addCTEs(query) { query.ctes.push( { alias: "_versions", columns: [ { columnName: "plan_id", dbType: "int" }, { columnName: "version_id", dbType: "int" }, ], query: { kind: "raw", bindings: this.#versions.flatMap(([pId, versionId]) => unsafeDeTagIds([pId, versionId])), sql: `SELECT * FROM (VALUES ${this.#versions.map(() => "(?::int,?::int)").join(",")}) AS t (plan_id, version_id)`, }, }, // Do the same thing for _plan_versions query.ctes.push(...); }}This is very high-level pseudo-code but the gist is:

- We’ve mutated the query to use our

_authorsCTE instead of theauthorstable - We’ve injected the

_authorsCTE, creating it dynamically based on theAuthorMetadata - We’ve injected our

_versionsand_plan_versionsconfig tables

After the plugin’s beforeFind is finished, Joist takes the updated query and turns it into SQL, just like it would any em.find query, but now the SQL it generates automatically reads the right versioned values.

4. Performance Evaluation

Section titled “4. Performance Evaluation”Now that we have everything working, how was the performance?

It was surprisingly good, but not perfect—we unfortunately saw a regression for reads “going through the CTE”, particularly when doing filtering, like:

WITH _versions (...), _plan_versions (...), _authors (...),)-- this first_name is evaluating against the CTE resultsSELECT * FROM _authors a WHERE a.first_name = 'bob'We were disappointed b/c we thought since our _authors CTE is “only used once” in the SQL query, that ideally the PG query planner would essentially “inline” the CTE and pretend it was not even there, for planning & indexing purposes.

Contrast this with a CTE that is “used twice” in a SQL query, which our understanding is that then Postgres executes it once, and materializes it in memory (basically caches it, instead of executing it twice). This materialization would be fine for smaller CTEs like _versions or _plan_versions, but on a potentially huge table like authors or plan_package_scope_lines, we definitely don’t want those entire tables sequentially scanned and creating “versioned copies” materialized in-memory before any WHERE clauses were applied.

So we thought our “only used once” _authors CTE rewrite would be performance neutral, but it was not—we assume because many of the CTE’s columns are not straight mappings, but due to some nuances with handling drafts, ended up being non-trivial CASE statements that look like:

-- example of the rewritten select clauses in the `_authors` CTESELECT a.id as id, a.created_at as created_at, -- immutable columns a.type_id as type_id, -- versioned columns (CASE WHEN _a_version.id IS NULL THEN a.first_name) ELSE _a_version.first_name END) as first_name, (CASE WHEN _a_version.id IS NULL THEN a.last_name) ELSE _a_version.last_name END) as last_name,And we suspected these CASE statements were not easy/possible for the query planner to “see through” and push filtering & indexing statistics through the top-level WHERE clause.

So, while so far our approach has been “add yet another CTE”, for this last stretch, we had to remove the _authors CTE and start “hard mode” rewriting the query by adding JOINs directly to the query itself, i.e. we’d go from a non-versioned query like:

-- previously we'd "just swap" the books & authors tables to-- versioned _books & _authors CTEsSELECT b.* FROM books JOIN authors a ON b.author_id = a.id WHERE a.first_name = 'bob';To:

SELECT -- rewrite the top-level select b.id as id, -- any versioned columns need `CASE` statements (CASE WHEN bv.id IS NULL THEN b.title ELSE bv.title) AS title, (CASE WHEN bv.id IS NULL THEN b.notes ELSE bv.notes) AS notes, -- ...repeat for each versioned column... -- ...also special for updated_at...FROM books -- keep the `books` table & add a `book_versions` JOIN directly to the query JOIN book_versions bv ON (bv.book_id = b.id AND bv.first_id >= pv.version_id AND ...) -- rewrite the `ON` to use `bv.author_id` (b/c books can change authors) JOIN authors a ON bv.author_id = a.id -- add a author_version join directly to the query JOIN author_versions av ON (av.author_id = a.id AND av.first_id >= pv.version_id AND ...) -- rewrite the condition from `a.first_name` to `av.first_name` WHERE av.first_name = 'bob';This is a lot more rewriting!

While the CTE approach let us just “swap the table”, and leave the rest of the query “reading from the alias a” & generally being none-the-wiser, now we have to find every b alias usage or a alias usage, and evaluate if the SELECT or JOIN ON or WHERE clause is touching a versioned column, and if so rewrite that usage to the bv or av respective versioned column.

There are pros/cons to this approach:

- Con: Obviously the query is much trickier to rewrite

- Pro: But since our rewriting algorithm is isolated to the

VersioningPluginfile, we were able to “refactor our versioned query logic” just once and have it apply everywhere which was amazing 🎉 - Pro: The “more complicated to us” CTE-less query is actually “simpler to the Postgres query planner” b/c there isn’t a CTE “sitting in the way” and so all the usual indexing/filtering performance optimizations kicked in, and got us back to baseline performance

Removing the _authors / _books CTEs and doing “inline rewriting” (basically what we’d hoped Postgres would do for us with the “used once” CTEs, but now we’re doing by hand) gave us a ~10x performance increase, and returned us to baseline performance, actually beating the performance of our original “write to drafts” approach. 🏃

Skipping Some Details

Section titled “Skipping Some Details”It would make the post even longer, so I’m skipping some of the nitty-gritty details like:

- Soft deletions—should entities “disappear” if they were added in v10 and the user pins to v8? Or “disappear” if they were deleted in v15 and the user is looking at v20?

- Initially we had our

VersionPluginplugin auto-filter these rows, but in practice this was too strict for some of our legacy code paths, so in both “not yet added” and “previously deleted” scenarios, we return rows anyway & then defer to application-level filtering

- Initially we had our

- Versioning

m2mcollections, both in the database (store full copies or incremental diffs?), and teaching the plugin to rewrite m2m joins/filters accordingly. - Reading

updated_atfrom the right identity table vs. the versions table to avoid oplock errors when drafts issueUPDATEs using plugin-loaded data - Ensuring endpoints make the

pinandaddPlugincalls without accidentally loading “not versioned” copies of the data they want to read into theEntityManager, which would cache the non-versioned data, & prevent future “should be versioned” reads for working as expected. - Migrating our codebase from the previous “by hand” / “write to drafts” initial versioning approach, to the new plugin + “write to identities” approach, which honestly was a lot of fun—lots of red code that was deleted & simplified by the new approach. 🔪

Thankfully we were able to solve each of these, and none turned into dealbreakers that compromised the overall approach. 😅

Wrapping Up

Section titled “Wrapping Up”This was definitely a long-form post, as we explored the Homebound problem space that drove our solution, rather than just a shorter announcement post of “btw Joist now has a plugin API”.

Which, yes, Joist does now have a plugin API for query rewriting 🎉, but we think it’s important to show how/why it was useful to us, and potentially inspire ideas for how it might be useful to others as well (i.e. an auth plugin that does ORM/data layer auth 🔑 is also on our todo list).

That said, we anticipate readers wondering “wow this solution seems too complex” (and, yes, our production VersionPlugin code is much more complicated than the pseudocode we’ve used in this post), “why didn’t you hand-write the queries”, etc 😰.

We can only report that we tried “just hand-write your versioning queries”, in the spirit of KISS & moving quickly while building our initial set of version-aware features, for about 6-9 months, and it was terrible. 😢

Today, we have versioning implemented as “a cross-cutting concern” (anyone remember Aspect Oriented Programming? 👴), primarily isolated to a single file/plugin, and the rest of our code went back to “boring CRUD” with “boring reads” and “boring writes”.

Our velocity has increased, bugs have decreased, and overall DX/developer happiness is back to our usual “this is a pleasant codebase” levels. 🎉

If you have any questions, feel free to drop by our Discord to chat.

Thanks

Section titled “Thanks”Thanks to the Homebound engineers who worked on this project: Arvin, for bearing the brunt of the tears & suffering, fixing bugs during our pre-plugin “write to drafts” approach (mea cupla! 😅), ZachG for owning the rewriting plugin, both Joist’s new plugin API & our internal VersioningPlugin implementation 🚀, and Roberth, Allan, and ZachO for all pitching in to get our refactoring landed in the limited, time-boxed window we had for the initiative ⏰🎉.